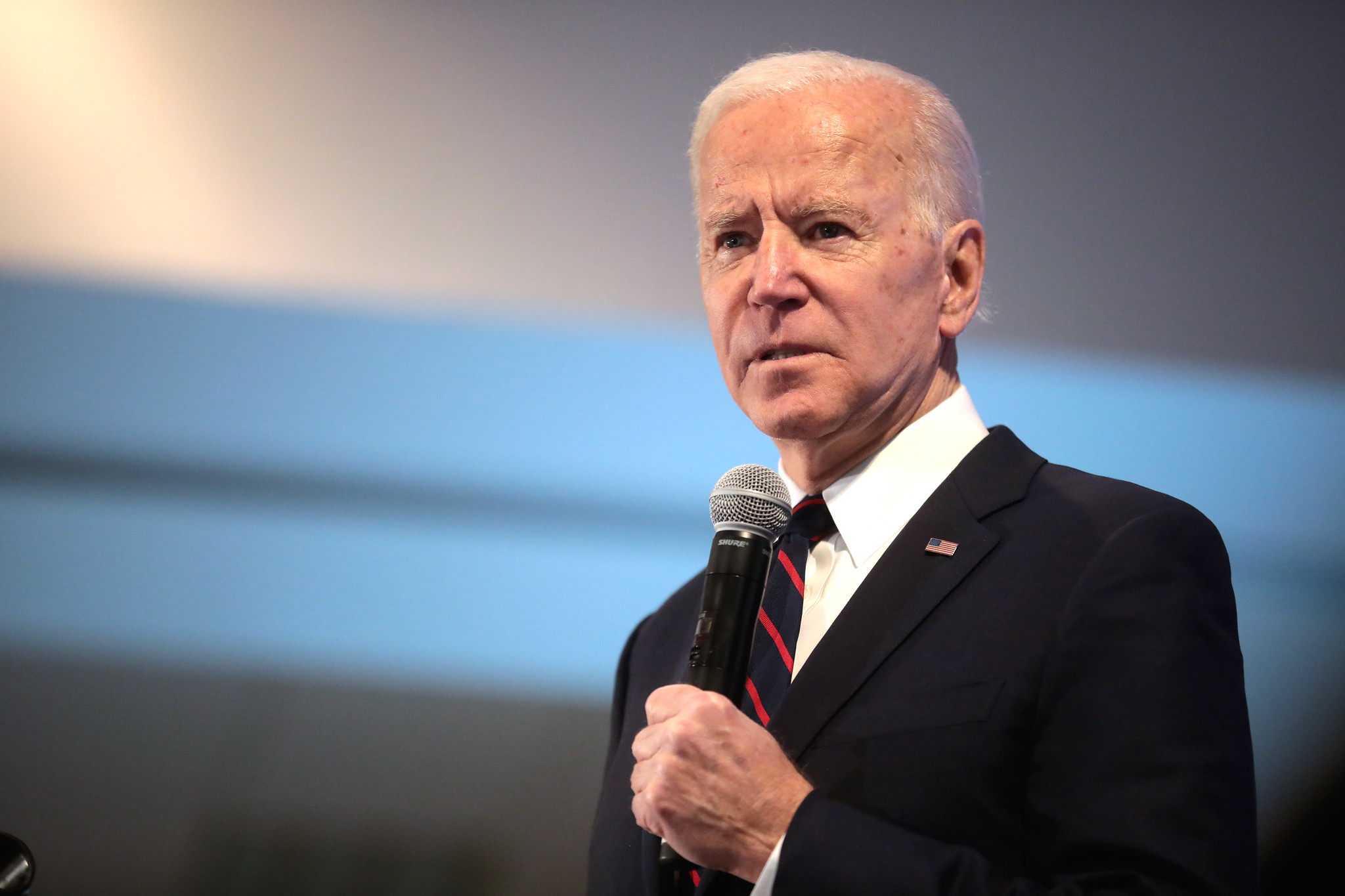

What President Biden could mean for Central Asia

As President-Elect Joe Biden prepares for government, his transition team looks to reclaim American foreign policy from Trump-era isolationism. President Trump had famously declared “America first”, a motto which, at the onset of the First World War, was originally used to define a vision of neutrality.

Accordingly, the Trump administration made a habit of retreating from international initiatives, be it the Iran Nuclear Deal, the Paris Climate Accords or, most recently, the World Health Organisation (WHO). Joe Biden will likely seek to reverse course, a direction made more evident by his reported intention to nominate Antony Blinken, an ardent internationalist, to head the US State Department.

This could prove welcome news for Central Asia, a region heavily dependent on foreign aid contributions. USAID, the agency responsible for international development, had seen repeated attempts at budget cuts throughout Trump’s tenure, proposals which would have had an outsize impact on Central Asia.

Such moves were consistently blocked by Congress. However, USAID was nevertheless disrupted by Trump-loyal political appointees. Even with an intact aid budget, American priorities had shifted away from development, particularly with regards to Central Asia, and towards a greater focus on national security.

The incoming Biden administration will likely oversee a renewed emphasis on international development, accompanied by a multilateral approach to foreign policy. According to George Ingram of the Brookings Institution, it would mean a “significant shift in attitude towards development and foreign aid” and an approach that is less “transactional” and more “strategic”. Blinken himself had previously signalled a “significant shift in attitude towards development and foreign aid”, while experts expect a return to normality and stability.

For Central Asia, this could mean increased funding for NGOs, money which dried up substantially following the global financial crisis and then again when the Trump administration oversaw a downward trend in American-sponsored activity.

For Joe Biden, development might also be part of a wider effort by his administration to combat Chinese influence. Even before Trump took office, and especially following a winding down of American military presence in Afghanistan, Chinese development efforts had already dwarfed those of its Western counterparts. Since 2013, Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative had seen billions of dollars spent on infrastructure in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and other Central Asian countries.

The issue is also not just of political and economic will. Unlike the United States, Chinese policymakers do not have to contend with concerns around human rights and Democracy promotion, a key advantage in a region largely comprised of fellow authoritarian states. While a renewed American focus on development might help level the playing field and expand Washington’s influence, it is highly unlikely to match Beijing’s ambitions. Regardless, the region at large can only benefit from this competition.